Your cart is currently empty!

Karen Horney’s theory of personality

The below is taken from Neurosis and Growth (Karen Horney, 1951), as well as summaries and commentaries from here and here and occassionaly my own reflections along the way.

–

Karen Horney was an amazing woman.

She immensely respected Freud but challenged much of psychoanalytical orthodoxy. She provided a theoretical framework of mental illness that is more aligned with our current understanding of trauma development in childhood.

She developed an understanding of the mind that was more inclusive of women and considerate of the impact of culture on the person. For example, she reasoned that women weren’t actually envious of men’s penis, but rather resentful of the structural power they held.

And she pursued an interest in spirituality in later life, curious about Zen Buddhism and how their ideas of enlightment mapped to the idea of self-actualisation in Western psychology.

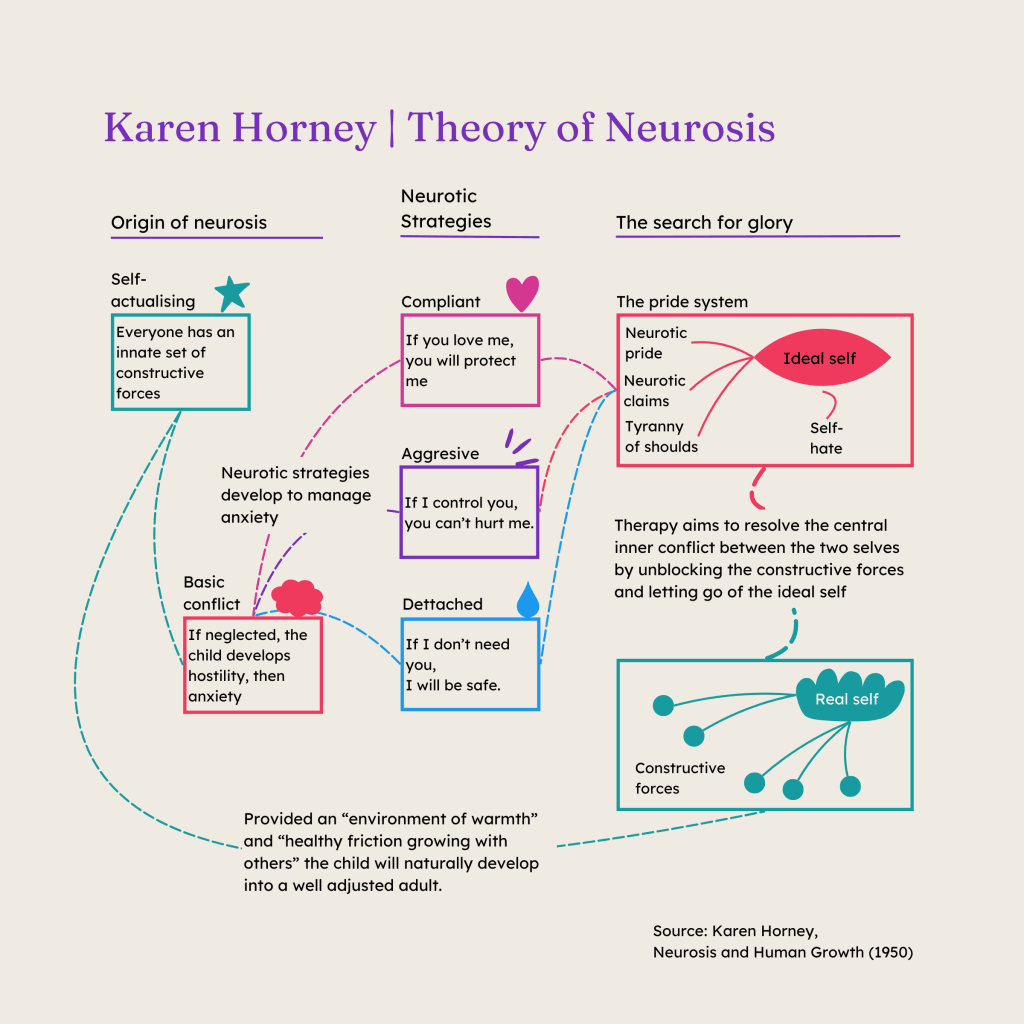

We all have it: the self-actualising tendency

She believed that humans have an innate need to develop themselves to their full potential, through the constructive forces of the self-actualising tendency, made up of our unique strengths and gifts.

In this, she was aligned to positive psychologists like Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers, who considered self-actualisation the driving force of human development.

However, unlike Rogers and Maslow (neither of them medical doctors), she was less interested in universal development and theories of personality, but rather focused on what happens when things go wrong. Perhaps also because, with an authoritarian father, she had been emotionally neglected herself.

For her, psychoanalysis was the key to unblock those constructive forces that naturally give way to the natural development of the person.

What is neurosis?

Today we don’t speak of neurosis, unless we mean a cluster of anxiety disorders in the bio-medical model (OCD, GAD, etc).

At the time, she postulated that neurosis is a “special form of human development that wastes the constructive forces”. It is “antithetical to growth”, which Horney understood not as a striving for perfection, dominance, power, or achievement, but rather as “free, healthy development according to one’s unique’s nature”.

In short, Horney was focused on the effects of childhood trauma on human’s feelings, thoughts and behaviour. Her work, pioneering at the time, still feels relevant and elegant today in explaining the psychosocial dynamics at play not just in anxiety, but also attachment, personality, mood and psychotic disorders.

Neurosis is a special form of human development that wastes the constructive forces

Karen Horney

What’s the origin of trauma?

Horney believed the person can develop themselves naturally. However, they need an “environment of warmth to give them the feeling of inner security and freedom to have their own feelings and thoughts, and express them…as well as the healthy friction of growing with others”.

Children develop trauma when their parents are “too wrapped up in their own neuroses”. Narcissistic, histrionic, alcoholic or otherwise emotionally immature parents are unable to love their children properly. Therefore, they sabotage the right environment giving rise to the basic conflict.

If the person can grow with others, in love and friction, they will also grow in accordance to the real self

Karen Horney

What is the basic conflict?

When natural development is blocked by the basic conflict, neurosis develops.

It is not as important the specifics of what happened during the formative years. What matters is whether the myriad of experiences in the child’s life lead to a feeling of being isolated and helpless in a hostile world.

This results in the basic (fundamental) anxiety, which prevents the child from spontaneously relating to others. And with this, an alienation from the real self, which the person has started disowning to alleviate their anxiety.

The child is now blocked from discovering who they may become, and instead strategically obsess about who they should be. Survival is at stake.

This is the basic conflict: when the child that feels in danger will start behaving in ways that feel safe, even if they are nonetheless in conflict with the wellbeing of others and themselves – a fact the person may only learn about in adulthood.

The three neurotic strategies

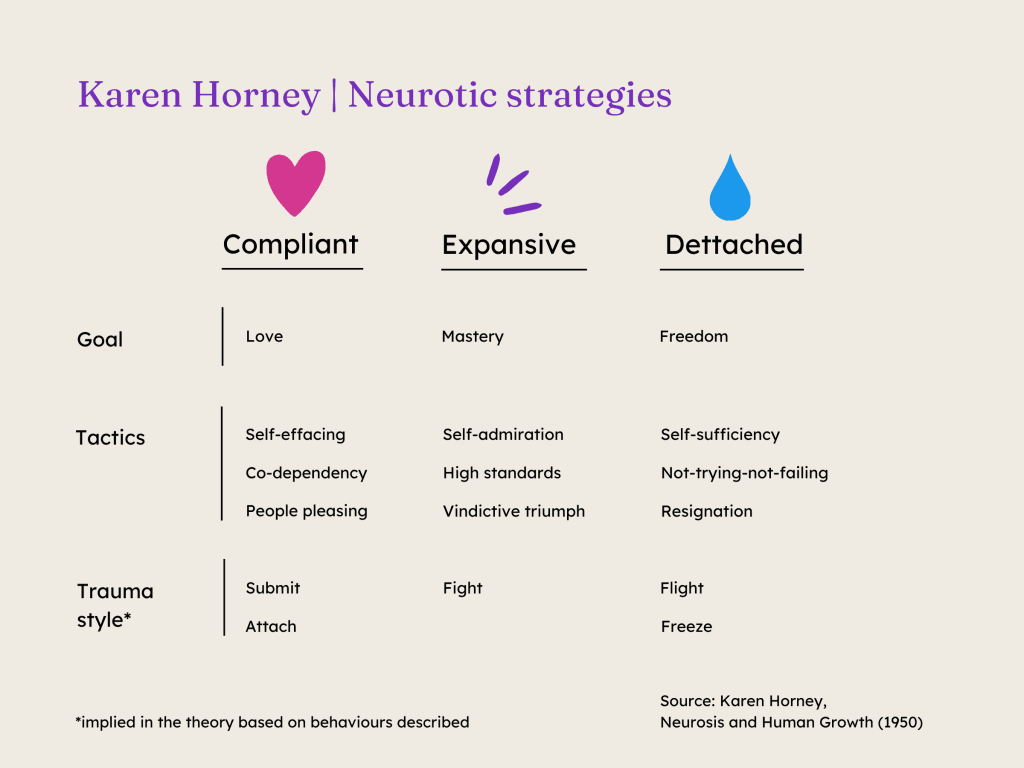

Once the child is plagued with this basic conflict, three neurotic attitudes may emerge: to love and comply, to compete and expand and to develop self-reliance and detach.

These are coping strategies that allow the traumatised child to mould themselves into the most effective way to get their needs met.

Horney proposed that the neurotic person will be stuck in the maladaptive use of these otherwise helpful attitudes. It is good to love other and seek love. It is good to strive towards achievements and wanting to the best one can be. It is good to be self-reliant. But it’s when one any of these tendencies become absolute, rigid and ultimately limiting and harmful that neurosis emerge.

This is as opposed to being able to flexibly integrate and regulate these styles to fit relevant everyday situations.

Neurotic trends can be grouped in three main strategies: compliant (moving towards people), expansive (moving against people) and detached (moving away from people).

However, it’s important to understand that even if people may err on a group of strategies, often their unconscious structure will be formed by layers of different trends.

For example, a narcissist people may be primarily expansive and against-people in some scenarios: competitive, aggressive, domineering.

However they may also have a vulnerability and need to be accepted and liked through compliance to others they feel are superior to them, whilst also having a deep need to not need anyone’s help to achieve their goals.

Untangling the complexity of how trends support each other to uphold the neurotic structure to prevent the basic anxiety is the process of psychoanalytical work that Horney saw as unblocking of the creative forces.

Neurotic trends “moving towards people”

The main goal of this group of trends is love. If people love them, they reason, they will be safe.

To achieve this, they use the compliant strategy, which is about giving up on one’s wishes and submit to protective people in their lives: a partner, parents, bosses.

The person will develop self-effacing attitudes: they’re not clever enough, pretty enough, experienced enough. They will form morbid co-dependency and people-pleasing attitudes to feel liked, protected and ultimately safe through the power of love.

Neurotic trends “moving against people”

The main goal is mastery. If they are in control of others and have some tangible and demonstrable superiority, they will be safe.

Horney proposes three different expansive strategies: narcissistic, perfectionist and vindictive.

Narcissistic use self-admiration as the driving force. They use methods to surround themselves with experiences that makes them feel superior and entitled.

Perfectionists use high standards as a way to protect themselves. They seek to be better than anyone else, as the only sure way to stay safe.

Vindictive see it as a fight against people and derive special pleasure when their gains are against someone they don’t like in a zero-sum game.

Three different flavours of mastery over others and the environment feels the only way to survive, yet it’s exhausting and a particularly alienating style.

Neurotic trends “moving away from people”

The main goal is freedom. If they are free and not reliant on others, they will be safe.

To achieve this, they use the detached strategy: of needing nothing and nobody to survive.

They use self-efficiency, as well as not-trying-not-failing and resignation as the tactics upon which they can achieve the particular flavour of low-responsibility freedom they equate with safety.

The search for glory

Alongside neurotic strategies, people with adverse childhood may embark on a search for glory; a pursuit of the ideal self figure, which is sadly not built upon the the constructive forces of our self-actualising tendency, but on the shaky ground of our imagination.

This search for glory is executed by the person’s neurotic strategy: guided by love, mastery or freedom.

The pride system

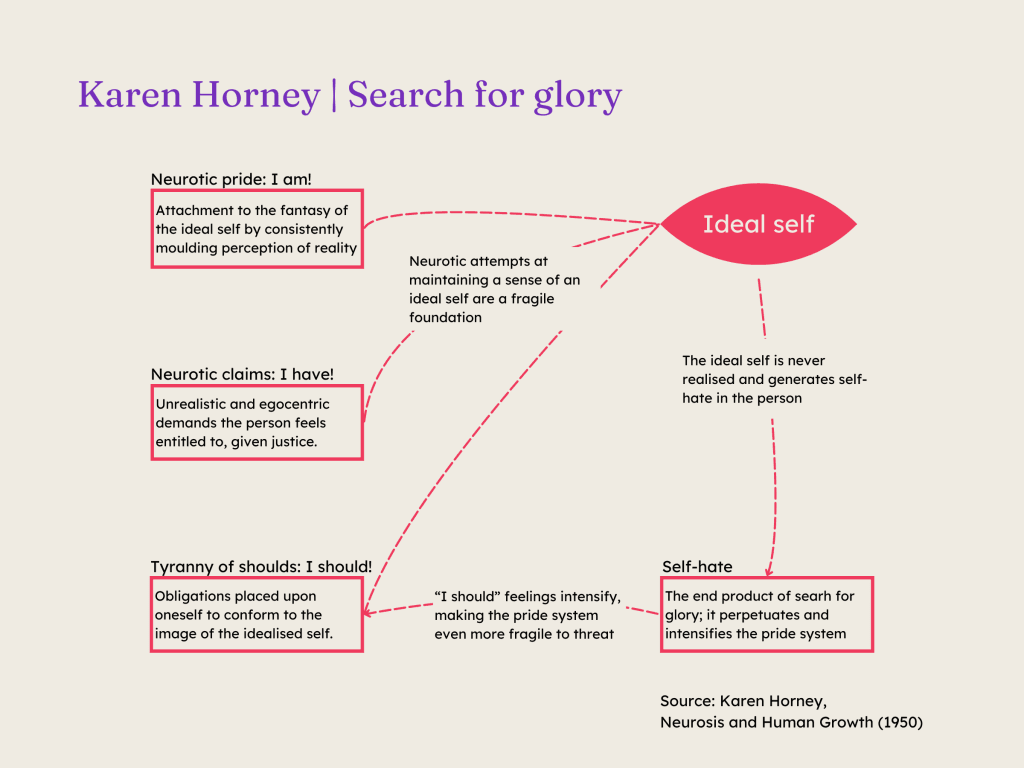

Psychologically, it is supported by the pride system: three interacting processes in how we relate to the world and ourselves: neurotic claims, neurotic pride, the tyranny of shoulds and, finally, its end product: self-hate.

The neurotic pride is the mechanism of protection of the ideal self, moulding our perception of reality to fit with our image of who we think we are (/should be seen as). It gives birth not only to our unique way to perceive the world with us in the centre, but also in how we demand others to treat us. Often this will take the form of neurotic claims,

Neurotic claims are particular expressions of unrealistic and egocentric demands (or complaints!) upon the environment or others. The person feels entitled to them, despite the fact they haven’t done the necessary effort to warrant them or simply lack the rational support for its entitlement.

Horney describes how people may use elaborate methods to exert their right to the claim appealing to a sense of justice or right in the world.

She succinctly described them as a feeling of entitlement to everything that is important to them.

With the tyranny of shoulds, the person intensifies their search for glory with an unrealistic self-development programme that is neither realistic nor true to their own nature. They may place impossible demands on them to be bigger, smaller, better, more lovable, more self-reliant, more successful and so on.

When the person faces aspects of reality that threaten the pride system, self-hate develops as its end product. The person finds themselves in an impossible bind and will keep intensifying the search for glory in a myriad ways, or breakdown into despair.

Ceasing the search for glory

The role of therapy is therefore to expose the pride system, support the person releasing from its tyranny, let go of the ideal self and unblock the constructive forces inherent in the individual to get in touch with their real self.

In doing so, people can resolve the central inner conflict and thus the anxiety of not feeling safe in the world.