Your cart is currently empty!

Games people play: A classified list of Eric Berne’s games in Transactional Analysis

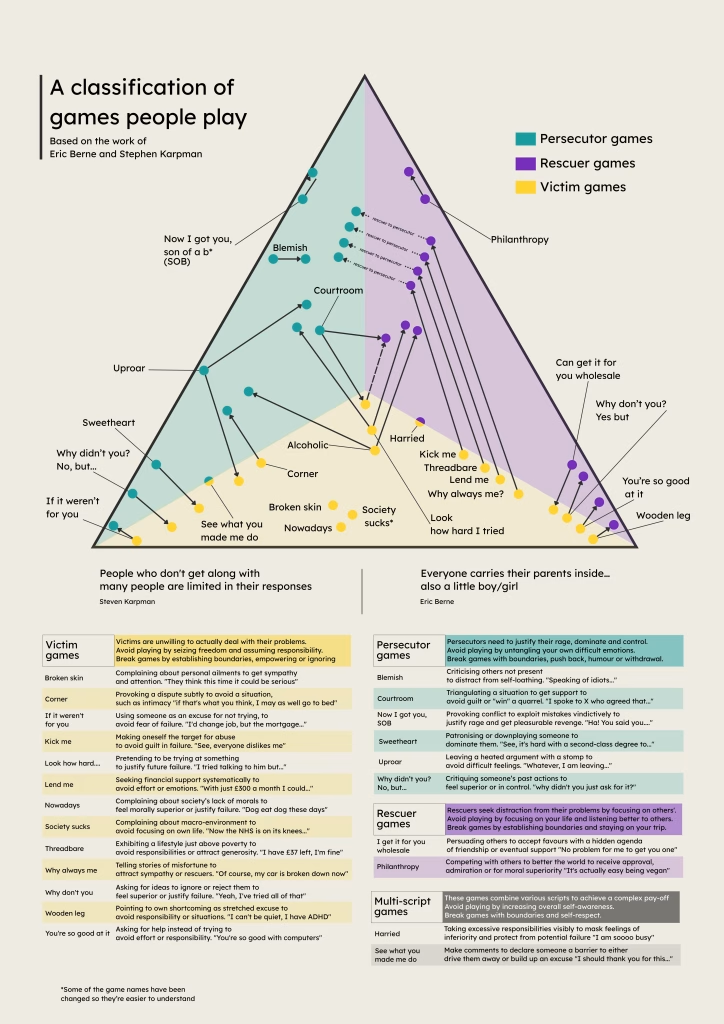

This article brings together two frameworks from Transactional Analysis: “Games” from Eric Berne (Games people play) and “The Drama Triangle” from Stephen Karpman.

–

Our thoughts and behaviours are often guided by unconscious scripts we’re following – whether it takes us a minute to realise, or years.

Uncovering those scripts – and in the process discovering the real us – can be made easier and more efficient with a map.

This was the focus of Eric Berne, who founded Transactional Analysis and developed the theory behind ego estates. In a previous post, I discussed how ego estates can be in conflict within ourselves.

Games takes this idea further by describing a list of common scenarios involving people on Parent or Child ego states.

Games are a series of “transactions” between individuals (a turn of speaking, a hug, closing the door on someone’s face, paying for someone’s drink) that lead the player who sets the game up to a pay-off (e.g a favour, a feeling, be left alone, having their drinks paid). This designed-for outcome is hidden from the other involved parties in the game, but also hidden from the main player too – who is unconscious of their concealed motivation.

You can buy this image as a poster.

The person who sets the game up has the most to get out of it, but it should be obvious nobody really wins in a game. If the game is played well, most of the players will get their pay-off (that’s why we play when we do!) but in reality they are only reinforcing their own barriers to wellbeing: avoidance of fears, conditional self-love, need for power, parental protection in an adult world, etc.

Nobody wins in a game

The drama triangle

A few years later after the publication of Berne’s “thesaurus of games”, one of his students, Stephen Karpman published the Drama Triangle which very elegantly posits that in drama-intense and/or manipulative relationships there are three main scripts: victim, rescuer and persecutor.

So whilst games in the context of transactional analysis is concerned with enabling detailed analysis of specific games to uncover unprocessed and unconscious mechanisms, the drama triangle offers a intuitive way to detect and label resentment, manipulation, co-dependency, vindication, abuse and other issues in relationships.

Victim, Rescuer and Persecutor scripts

In Transactional Analysis, we talk about scripts rather than people, because those scripts are but a small and temporary part of the person. And in fact, it’s common for people to switch between these scripts victim, persecutor or rescuer – sometimes in the same interaction.

A victim is a script that leads someone to not feel able to take care of their own life. Because of this, they will enlist others to help take care of diverse physical, financial, emotional and psychological needs.

A rescuer is a script which needs to feel like they are helping others. Because of this, they will be attracted to victims who offer endless opportunities for helping and for modelling someone not “as good” as them – this helps their feelings of self-worth.

A persecutor is a script which antagonises others in the pursuit of control, power and to avoid facing fears. Because of this, they will seek, find or make up enemies and other focus objects/ideas to release their anger with.

Overview of games

In every game there is:

- an agent – who makes the first move and thus sets the game up. The agent will always start from a drama-position making each game either a victim, rescuer or persecutor game – or a hybrid.

- involved parties – who can continue and fuel the game, or avoid it in a specific way.

Games can be played by two-to-many players even if a couple of the games (multi-script games) don’t particularly require other players

- possible directions – sometimes games can lead an involved party to change script. A rescuer on a victim-rescuing game such as “lend me” can switch to persecutor and suggest to play “why didn’t you – no, but” next time.

Pointless games (ain’t it awful)

Pointless games are simple victim games who don’t need rescuers, persecutors and neither have a particular sense of direction.

People playing this game take on a victim script to complain about something to get sympathy, evasion from responsibilities or relief from a pressure to achieve. Depending on the ego state, it can be played in a parent version (nowadays), adult version (broken skin) and child version (society sucks)

- Nowadays. Players complain about things that aren’t as good as they used to be, particularly when things don’t align to their values, beliefs and behaviours. This offers players narratives to justify their external problems, whilst feeling vaguely superior.

- Broken skin. Players discuss injuries, diseases and other reasons-for-sympathy. Often they help the player justify their wider positions in life, which they feel it’s not what it should be.

- Society sucks. Players pick stories from the news to make a case about how society or the government sucks and would work better if they implemented their ideas. It can be combined with “Nowadays” (1) to really bring on the bad vibes, or transformed into a relatively benign game of “Indigence” or “Busman’s Holidays”, or a more toxic variation with a persecutor game with “Now I got you son of a bitch”

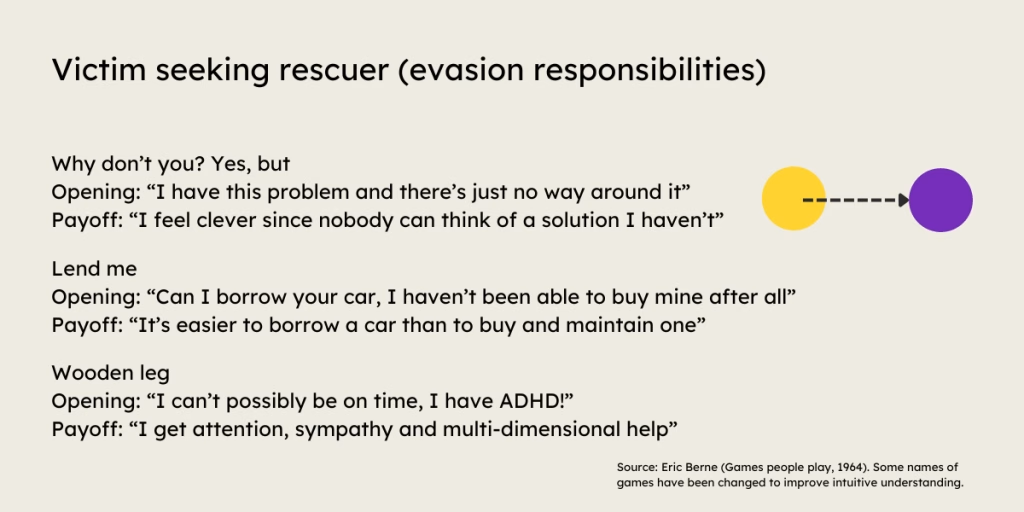

Victim seeking rescuer games

These are quite popular games. It may be because someone on a victim script may still have objective physical, financial, emotional and psychological need for support. This attracts these people to those who are on a complementary rescue script. The major risk of this games is for the rescuer to end up burnt out and moving towards persecuting games.

- Why don’t you? Yes, but. This game is an evolution of the pointless victim games. Still fairly pointless, it however requires a light rescue player. The agent who starts the game will bring an issue to the table and invite suggestion to then routinely turn each of them down as something they tried or thought of. The agents gets the satisfaction of turning down those solutions and making evident that nobody could solve this problem. So, how could they?

- Threadbare. Players will refrain from achieving financial independence and will prefer instead of being supported and cushioned from responsibilities and more importantly, the emotional difficulties that come with earning a living and taking responsibility for their lives.

- Kick me. Players make efforts that it be known about their difficulties, challenges

- Lend me. Players here need small-ish amounts of money to finish the month. It could anything beyond money. The player gets satisfaction from being looked after. If the game is benign, the player will be a minor annoyance and repay his debts. But it can escalate into a game of “Messy”.

- Why does this always happen to me? Players take a pointless game of “Society sucks” and aim it towards more active victim-calling. “Why does my driving licence expire just when I need the car and so can you please drive me?”

- You’re so good at it. Players may engage in this game for more tactical help – with computers, an engineering exam or doing admin. This is quite a benign game because the rescuer does get a lot of praise that they appreciate. A slightly toxic version of this game is when someone on a victim script manipulates a rescuer into labour and favours with the implied promise of a developing romantic relationship that never quite arrives.

- Wooden leg. Players use a wooden leg (a back pain, a mental health diagnosis or a wooden leg) as the over-stretched reason why they need someone to help them with things they could do, and would benefit from, doing themselves. This is obviously different from actively getting the appropriate help for any health condition, which is a no-drama no-game stance.

Victim seeking persecution games

These games tend to be marital, where ongoing persecution (even if with script switches) is more plausible. Players of these games can be looking for a justification of their life choices or a passive.

- If it weren’t for you. Players use a significant other as the excuse as to why they can’t do this thing they really want to do but are afraid of. It doesn’t matter if the other person takes on a persecuting role or whether it’s more of an imagined role in the agent’s game. For example, someone may complain they can’t change careers because of family-related financial obligations and obtain the double satisfaction of not having to face their fears as well as being wronged and owed.

- Corner. Players here will seek to avoid any form of intimacy by subtly forcing a fallout. The person who makes the original move will use the reaction from the other player as a method of argumentative escalation. For example

- Player A – ah yes, I had to tell you about this bill that came out.

- PLayer B – seriously? it’s 9pm!

- PLayer A – well, if that’s your mood today I rather be on my own, thank you. (I win)

Rescuer seeking victim games

In a rescue seeking victim game, the player who sets the game up – is looking to feel valuable or morally superior, or else set up a situation where they get control or power to use at a later stage.

- Can get it for you wholesale. In this game, someone is trying to offer an edge, skill or other advantage to someone else. The rescuer have internal motivation to feel capable but also may be setting the scene for co-dependency. It could also be they benefit from the help in other external ways, such as buying power.

Rescuer seeking rescuer games

- Philantrophy. In a game of philantropy – likely expansive narcissists in Karen Horney’s theory of neurosis – will compete to see how has done the most for the world. This could be from wealthy people comparing donations, to doctors, nurses, designers and – even – management consultants talking about how they improve people’s lives.

Persecutor to persecutor games

These games are used for persecutors to release unprocessed anger, alleviate tension or help each other feel superior.

- Uproar. In this game an argument escalates between (usually) two until one has an explosive argument and leaves the scene and usually shuts the door loudly. This helps the player release anger and escape the situation. It is particularly common in marriages.

- Blemish. The player here will engage another one to criticise third parties as a way to feel superior, avoid their own insecurities or any other perceived threat.

- Now I got you, son of a bitch. This intense game is set up when a player uses alleged evidence of wrongdoing to unleash all their anger. If directed at someone in particular – rather than say, a customer service team – the other person can play a short game on a complementary victim script (“I am sorry this has happened and it will never happen again”) or make it a double loss by taking a persecutor script (“and I will take you to court”).

Multi-script games

In multi-script games, players combine scripts for a more sophisticated, subtle transaction.

- Harried. Players here will take on rescue/hero script to become the best employee/parent/partner/homeowner/neighbour which makes them look amazing in front of these audiences, while stretching them enough as to gracefully take on a parallel victim script. The payoff is sadly either some kind of justifiable breakdown long-term, the set up of an eventual “Look how hard I tried”, and momentary strokes of self-worth.

“I only slept four hours from making the children’s Halloween costumes and the mini-muffins for the neighbours picnic”

- See what you made me do. Often for longstanding couples who have outgrown their co-dependency, this game is set up by someone complaining at the outcome of an interruption.

“Aggh, I lost my train of thought and I have this presentation tomorrow”

- It’s for you. In this game, a persecutor gifts something to someone to manipulate them into doing what they want. A teenager may get gifted posh clothes that pleases their parents but not them. A husband may gift a wife a subscription to healthy meals so that she loses weight.