Counselling skills are a cluster of learned and practised abilities that therapists use with clients to achieve the goals of therapy.

Developing these skills involves a combination of knowledge, practice, reflection and feedback.

Listening

Listening is a core counselling skill – it’s also frustratingly hard.

Growing up we’re told to control the narrative and dominate the conversation.

Even if we accept intellectually that good listening will improve our approach, we still find it difficult to not want to definitely contribute, satisfactorily conclude and absolutely confirm.

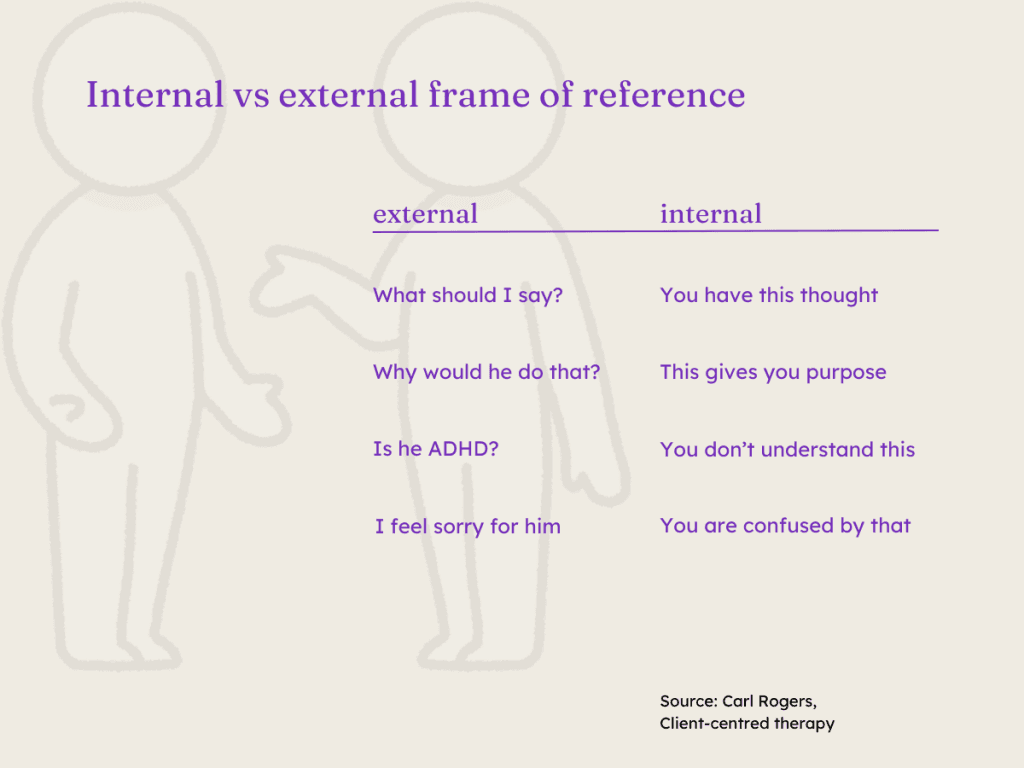

Listening as a counselling skill also takes on another level to good listening in everyday interaction. We don’t just want to process every word spoken (alongside all non-verbal communication), we also want to abandon our own frame of reference, so we can enter the other person’s.

This means putting aside every value and belief we hold so that we can get to see what the client’s world feels – to them.

Dave Mearns and Mike Cooper introduced the idea of “holistic listening” – a “breathing in, a beholding of the client” where attention is paid to everything, as opposed to a constant discernment of what seems to matter.

To display full-on listening skills alongside other core counselling skills can accelerate the depth of the relationship and the ability of the client to work productively during their therapy.

Silence

Silence is another crucial skill for a counsellor. It’s also one that takes on a rich, experiential quality for the client. It’s a big contributor to the “counselling zone”.

Silence is useful for the simple reason that it implicitly communicates to the client that they will be doing all of the work in the session – and therefore their lives. On top of that, silence allows the client to work in their mind with what will be at times a dramatic amount of new information, overwhelming feelings and new insight.

In “Client-centred therapy”, Carl Rogers quotes clients stressing the role of silence in their sessions.

“At first, his silence angered me. But then I felt there must be a purpose. I had to delve in my own mind deeper and deeper”

Here we can see that the silence isn’t comfortable at various conscious and unconscious levels. This is why we are so adept socially to avoid silence, which in most situations is a social faux pas and a clear sign that there isn’t chemistry.

So we agree with people. We laugh to the spirit of what people say. We resort to conversation starters and re-kindlers. We work on our humour and entertaining skills. We support each other with platitudes and words of encouragement. We watch the news so we have shallow things to talk about.

But of course, we also know silence to be a sign and facilitator of intimacy. This is the reason why we learn to cultivate it.

Silence is triggering for counsellors too, and – hear this – we need to bear both our own lack of comfort and the client’s which will be visible. One way to think about it is like staring contests that we played as kids.

Who can be silent the longest, lovingly and comfortably?

As another client puts it

“I had to put my concerns into words and logical sequences because I couldn’t keep silent longer than the counsellor”

Read about my explorations with silence

Reflecting

A reflection is a tentative interpretation from the counsellor towards the feelings of the client, or the meaning of those feelings.

Identifying and differentiating feelings and associated meanings is a key process of therapy and hence the counsellor here is helping the client put those under examination a bit more, whilst coming closer together in terms of the understanding of how it feels to be this client.

Reflecting on a feeling plays back a succinct interpretation of the dominating feelings behind a story in the past or a current state in the present.

– “Emily didn’t invite me to the party, when she knew how much it meant to me and the fact I invited her when she had no friends”

– You felt betrayed by your friend…

– “I just can’t believe he acts this way”

– “You feel surprised, but also upset about his behaviour”

Reflecting on a meaning focus on the client’s interpretation of a situation

– I am just worried that if she seems bored on the phone on our first date, what would it be like later?

– You think this shows little promise in a future relationship

Open questions

Early on, the counsellor has to acquire an overall understanding of the client’s situation.

Contrary to most other professional interactions where an expert asks many questions to a client to start diagnosing and solutionising, it’s important to keep our own curiosity at bay, as well as recognising that allowing the client to unfold their own story and concerns is more effective than influencing the scope of the conversation and where the client focuses his attention.

What the client chooses to talk about is data we lose when we make them speak of something in particular.

However. Clients vary in the openness with which they share, as well as the depth as to which they attack their problems.

One of the key agendas in counselling is to allow the client to travel deeper in to their feelings so that an integrating and organising process can take place. This can’t happen if a client is not sharing meaningful stuff.

Hence opening questions can facilitate deeper enquiry

– Tell me more about what you do with your friends when you meet up

– And how do you actually do that?

– So why travel so far?

Challenging

Once trust has been established and the client has reached a stage where contradictions are felt and noticed – or just as they start scratching that surface, a counsellor can choose to challenge a client to bring a contradiction to the table to be analysed in more depth. It can also be used for the client to take responsibility for aspects of their lives they are making up excuses for.

It’s crucially important that the counsellor is confident to be acting in the best interests of their client and to have established a safe, secure relationship where that can be done without to the clients perceiving a lack of empathy, or judgement.

However, it’s perfectly possible for the counsellor to challenge a client who with they are in a secure relationship just for the mere reason that the behaviour of the client is hard for the counsellor to understand, given their deep understanding of this person. The implication in this challenge is that the counsellor recognises not only that they don’t understand, but that the client might neither, and therefore it’s important to put a pin on it to look at it closer.

– …and then I told them I was done with the project and I finish tomorrow…

– oh, how comes? I thought you really cared about this work

It’s also likely that the counsellor has by now established a good map with the client on important values the client holds, as well as common ways in which a client self-sabotages themselves. Hence a challenge can be useful in protecting the client while encouraging movement.

In Love’s executioner, Irvin Yalom details extensive use of challenge to attempt important aspects of progress when patients are uncollaborative, shallow or simply lack psychological mindedness. It’s also true that these reported cases are often “last-ditch attempts” with clients who haven’t been successful in therapy before.

Despite the fact that his challenges seem harsh at times and may damage the relationship, they often work seem to work in the long term in securing key commitments in the client such as an assumption of responsibility and a pursuit of congruence.

Immediacy

Immediacy is a form of self-disclosure that focuses of the here-and-now of the therapy session. The therapist reveals how they feel at this moment in the context of the relationship or the client:

- I feel really inspired by your vision

- I am crying because I can feel the pain in that story

- I feel like you are keeping things from me

- I want to be really honest and say I am a bit bored – can we talk about that?

Immediacy can be effective at building alliance (as in the crying example) or as a way to bring an issue to the present and where “the other person is there to give their perspective”.

Yalom discusses this skill by saying:

“The therapist’s most valuable tool is the process focus. Process as opposed to content. Content refers to the actual words, whereas process reveals how the content is expressed and what the mode of expression is revealing about a relationship.

“I had to stop listening to what she was saying and instead focus on how we were relating to each other”

One way in which immediacy can emerge is transference interpretation: where the counsellor focuses on the relationship or own feelings to provide an hypothesis of a pattern outside of it. Example:

“I think you feel you are superior to me. And I feel hurt by that. I wonder if we can explore how this be happening in some of the stories we’ve been discussing”

Both immediacy in its simple form and transference interpretation are risky, can provoke negative feelings in the client and should only be used strategically and in the context of a strong alliance.

Summarising

At the end of a session or at key moments, the counsellor may summarise some of the points that were covered or attempt to establish a bird-eye view of the client’s reflection. This can help the client organise their thinking and come into it again.

– You talked about issues at work and how you were ready to try something different next week. Perhaps it’s worth getting to know this person a bit better. You also mentioned you feel your partner is distant, and how you feel ready to bring it up with them.

Using these skills in combination allows counsellors to build a trusting relationship, promote self-enquiry and facilitate change.

Do skills vary across modalities?

Counsellors of different modalities use a similar range of skills, however they may use them differently and to different degrees.

Humanistic counsellors are particularly interested in developing a relationship with the client and facilitating the emergence of self-responsibility. Therefore, skills like listening, silence and re-stating will be used very often.

On the other hand, a cognitive-behavioural counsellor is more directive in the interaction and therefore may challenge a client more often, but perhaps without much immediacy. For example, when compared with psychodynamic therapists, CBT therapists have been found to make around 50 per cent more utterances (Stiles et al., 1998).

This is because their underlying theoretical framework is different and therefore so is their approach.