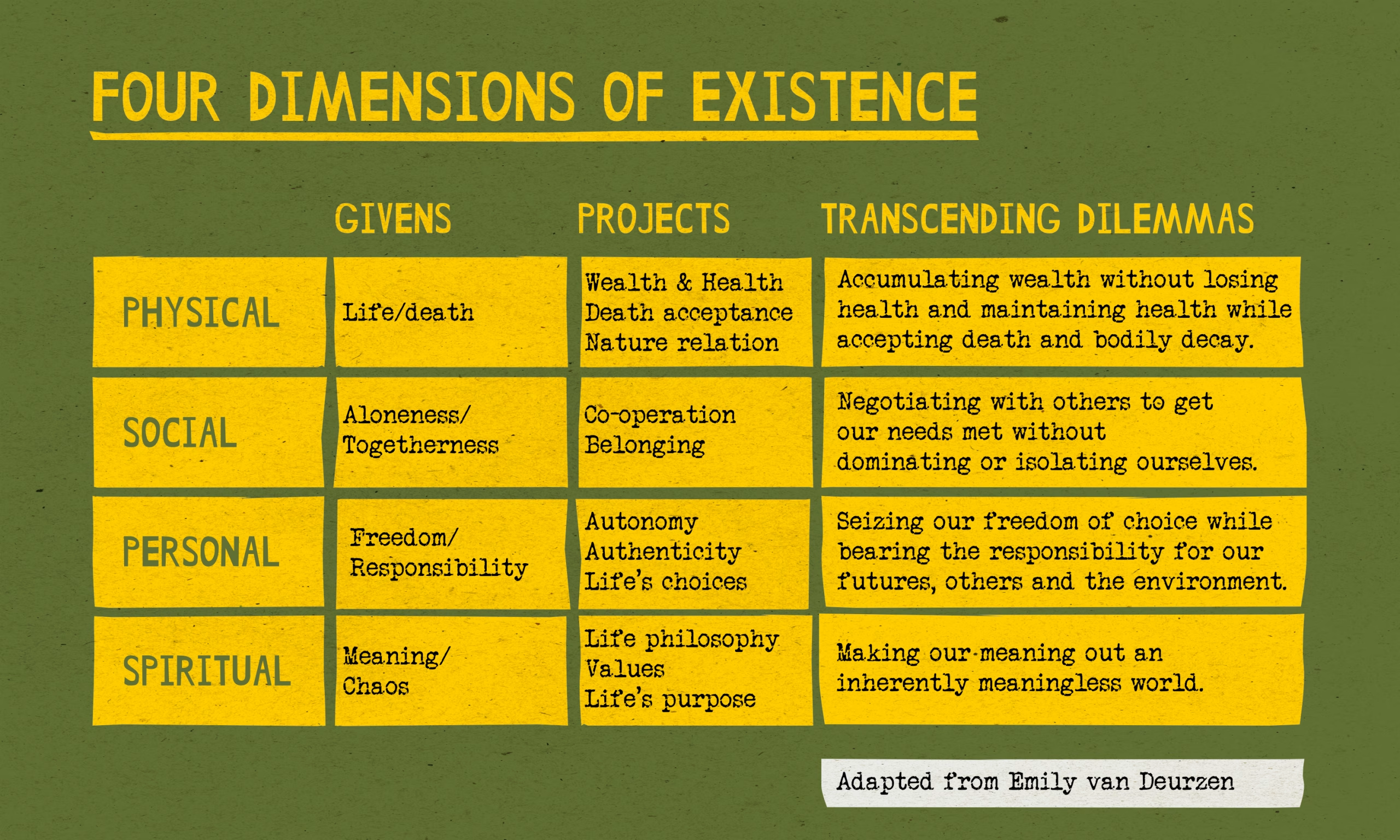

The Existential Map is a framework for existential therapy by Emmy van Deurzen that helps us live to our fullest expression by gaining mastery over life’s challenges and tribulations. It is made up of four dimensions of existence.

Each dimension is “a playground of paradoxes and contradictions” (Deurzen, Arnold-Baker, 2018) where our lives unfold with goals, projects and tensions within the overall givens of existence.

She developed this theory from the earlier work of Binswanger, who in turn built it from the Heideggerian concept being-in-the-world (Cooper, M. 2003).

The four dimensions are:

- The physical dimension: the place of our bodies, objects and the environment

- The social dimension: the place of our relationship with others

- The personal dimension: the place of being with ourselves as autonomous beings.

- The spiritual dimension: the place of ideas, values, meaning and purpose.

The four dimensions are deeply intertwined. Many scenarios may have significance in various dimensions at once. For example, getting ill may start in the physical dimension, then go on affecting our relationship with family members in the social dimension, our self-esteem and autonomy in the personal dimension and increase the value we put in self-compassion in the spiritual dimension.

To some extent, the four dimensions are sequential. We develop these dimensions in turn, as we cross different boundaries that define our experiences. A healthy dimension supports later dimensions, although it is also possible to use the development of a later dimension (such as personal and spiritual) to strengthen the more fundamental dimensions (such as social and physical).

For each dimension, we can consider the givens that limit our possibilities, the key projects that develop our mastery and the ways to transcend its paradoxes.

The physical dimension

The umwelt, or physical world, is the foundation of our experience and relates to our being in nature and to being bodies.

This dimension emerges from the boundary between our body with the environment.

It is I that is hungry/angry/sad, not the whole of existence. This may sound obvious, but it is easy to lose this perspective when we are angry and can’t self-reflect that this is just the way our bodies are feeling at a particular moment in time.

The fundamental limit of this dimension is that we have been born and we will die. Therefore, we have to live this life we have been thrown into. Mastery in this dimension is to live as well as possible accepting our lack of control of when it (and how) will end.

The main project is to stay alive by ensuring we have enough wealth and health. For this, we need to act in particular ways (we need to work, eat, sleep, exercise, go to the doctor). The projects in this dimension are deeply paradoxical: accumulating wealth may hurt our health, and looking after our health may risk our wealth. In turn, either a desire to be healthy or the accumulation of wealth naturally decreases our acceptance of mortality, aging and illness.

Another aspect of this dimension is our embodied relationship with our environment: from our places of dwelling and work, to the natural environment. A harmonious relationship with the natural systems we inhabit can be deeply healing for our bodies, as well as a source of meaning in the spiritual dimension.

When we struggle to ground our experience in our bodily existence we may develop issues such as eating disorders, addiction, phobias, compulsion or psychosomatic diseases (van Deurzen, 1997)

We may also struggle in forthcoming dimensions. We may find it difficult to set and respect boundaries with others (social dimension), or have a sense of autonomy (personal dimension). If we do develop a spiritual dimension, this may not be grounded in our physical manifestation leading to issues of spiritual bypassing or death avoidance.

The social dimension

The mitwelt – or social world – relates to our being with others.

This dimension emerges from the boundary between ourselves and others. It is in relation with others that we get to understand ourselves and have the foundation upon which we can build a “sense of me”, a key project in the next dimension: the personal.

The fundamental constraint in this dimension is that we are both alone and dependent on others to survive.

The main projects in this dimension are co-operation and belonging. The fundamental paradox is that we need to be able to stand our ground and negotiate with others to get our needs met, whilst at the same time be willing to compromise and respect others as subjective beings.

In this dimension, we analyse not only our relationship with our closed friends and family, but also the wider relationship with our social and political context. Someone not engaged in close relationships who may also not feel to belong in the society at large or attuned to the political milieu may be at risk as the repercussions are felt across all dimensions, clouding the person’s existence.

Those struggling with this dimension may not develop the right balance in relationships with others and may suffer symptoms of abusive behaviour, borderline, anti-social patterns, co-dependency, martyrdom, people-pleasing. (van Deurzen, 1997)

The personal dimension

The egenwelt – or personal world – relates to our being with ourselves.

This dimension emerges from the boundary we draw ourselves to separate what is me from what isn’t. The purpose of this boundary is to maintain a sense of continuity, crucial to make sense of the world, carry out our projects and develop a philosophy of life in the next dimension.

The constraints in this dimension are formed by the paradox that we are free to make choices and we bear the responsibility of those, the impact on other people’s lives and the environment upon which we depend.

The main projects in this dimension are autonomy, authenticity, defining a sense of me as a separate subjectivity and, finally, the facing of our radical freedom to make choices and deal with their consequences.

The paradoxical nature of this dimension is that we need to create a coherent sense of ourselves while being open to constantly refine who we may become through our own actions (ie, life as becoming). And that whilst we want to live authentic lives, we also need to make inauthentic choices to live peacefully with others.

Those struggling at this level may develop certain personality disorders (narcissism, schizoid).

The spiritual dimension

The uberwelt – or spiritual world – relates to our being.

This dimension emerges from taking a step back from all our boundaries and looking at our life in the abstract: from the meta viewpoint of ideas, values, overarching philosophy of life and our sense of life’s purpose.

This is the ultimate and central project: that of finding meaning for our existence, out of a world that offers none inherently. It asks of us that we determine how we want to live our lives and how we are going to make them count in our own eyes. Like Simone de Beauvoir says “it makes no sense to ask if life is worth living, we make it worth living through our choices”.

This is the final paradox we are contending with: there is no meaning and we have to find it. And how well we find it determines our appetite for living once the novelty has worn out.

Working with the four dimensions

Van Deurzen’s philosophy is not for the faint hearted: she urges us to face our givens, starting with our mortality so that it can “teach us how to live” (1997). She shows us that life is full of unresolvable paradoxes that we need to find a way to balance and make sense of them.

Yet once we accept that life is fundamentally tough, and that cravings, pain, uncertainty is part of it, we find the resolve to accept what is, while we constantly put the effort to make our lives the best they can be.

Bibliography

Cooper, M. (2016) Existential Therapies. 2nd edn. London: SAGE Publications.

van Deurzen, E. (2010) Everyday Mysteries: A Handbook of Existential Psychotherapy. 2nd edn. London: Routledge.

van Deurzen, E. and Arnold-Baker, C. (2018) Existential Therapy: Distinctive Features. London: Taylor & Francis (Routledge).

van Deurzen, E. (2015) Existential Counselling and Psychotherapy in Practice. 3rd edn. London: SAGE Publications.

van Deurzen, E. and Adams, M. (2016) Skills in Existential Counselling & Psychotherapy. London: SAGE Publications.