The search for the true self is like the search for the philosopher’s stone or Kung Fu Panda Dragon Scroll: both crucial and pointless.

Pointless because just like the philosopher’s stone it doesn’t really exist and therefore it can’t be discovered, per se. But crucial because it is in the journey of that search that we may find wisdom, wellbeing and better living.

Aesop’s fable of the farmer and his sons follows this mythical structure. A farmer on his deathbed tells the children not to divide the land as there is buried treasure. However upon digging and digging they fail to find anything. Frustrated, they stop, but soon they find that their work in the land softening the soil has gifted them with a good harvest.

The beginning of the search for the real self

We become urgent in our search for our real self when our current life starts not to feel right. In Campbell’s monomyth this is the first step, the call to adventure where “the familiar life horizon has been outgrown: the old concepts, ideals and emotional patterns no longer fit” (Campbell, J. 2008: 43).

Following the monomyth, we may cross some thresholds and abandon some of our comfortable old life. This may mean the end of jobs or entire careers, relationships or geographical locations.

On this journey through uncharted territory, we may face some trials, uncover some new insight and metaphorical riches and if we are lucky return as a wiser, rounded and well adjusted individual.

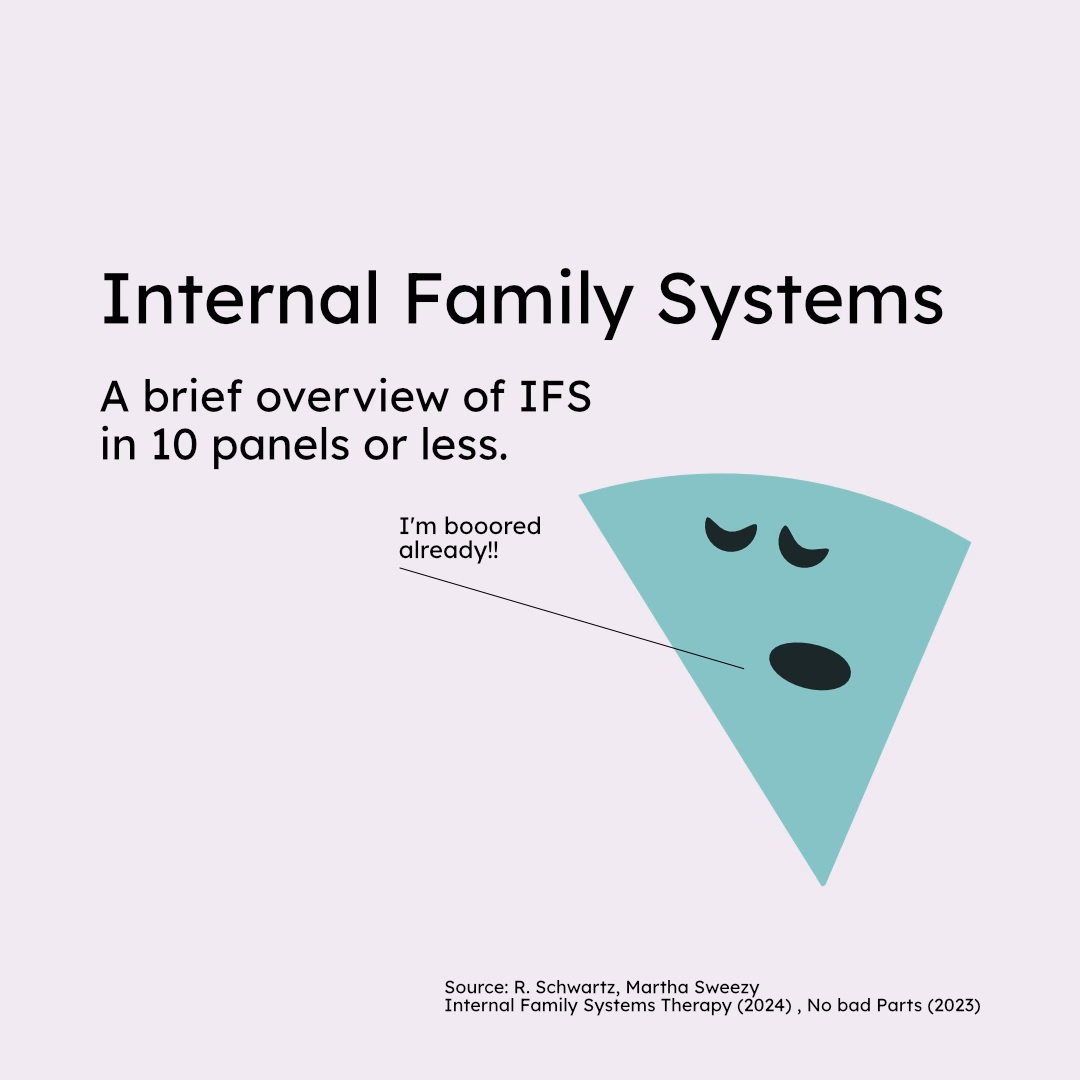

Winnicott’s model of the true/false self

The true self as a well defined construct originates in the theory of psychoanalyst Winnicott, with roots back to Freud’s concept of the unconscious defending difficult material from becoming conscious. But as Winnicott himself argues “poets, philosophers and seers have always concerned themselves with the idea of a true self” (Winnicott, D. 1964)

It goes like this: the genuine version of ourselves becomes hidden behind the facade of a false self as a child tries to cope with a situation for which their true self isn’t valid. The reactions from lack of politiness in front of parents, weakness in front of older siblings or laziness in front of teachers can develop the need for this false self, which in hiding a true(r) self becomes distant from authentic living and the organism itself.

Moving beyond the true/self model in the search for authenticity

Winnicott’s model of the true/false self is a helpful starting point to understand how people often become alienated from their own being in the world.

However, as a 50-years old theory it can do with some revisions:

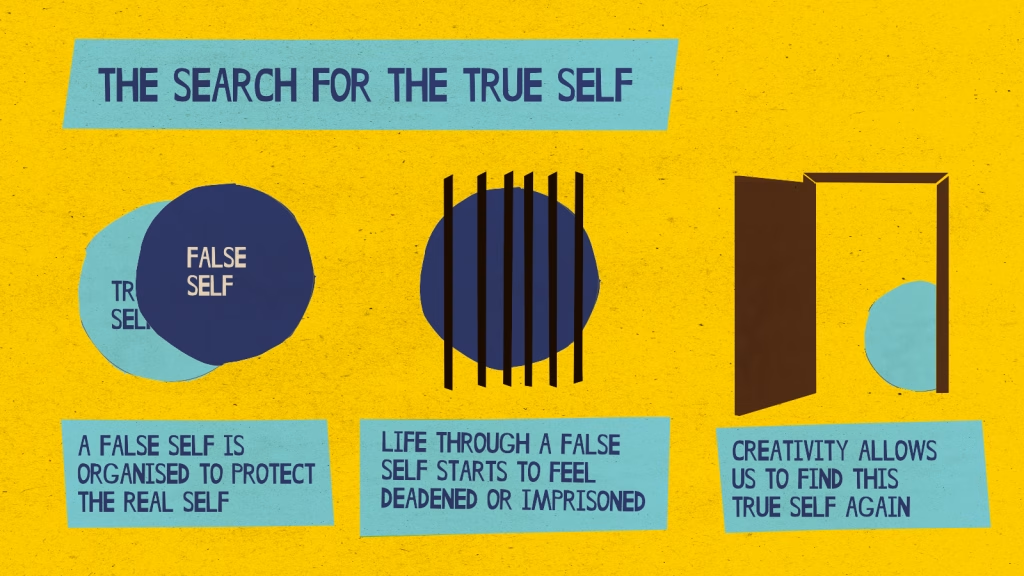

- It is helpful to think of the self as actioned (verb) through our choices within our constraints, rather than discovered or unblocked (noun).

- It is helpful to think of the self as a plurality of selves rather than just one.

- It is helpful to think of the self as a social and cultural entity, rather than just as an individual

The self as action of our choices

One of the issues with the true/self model is that errs towards essentialism and determinism. This happened, therefore now…

Psychoanalysts such as Winnicott privilege the past. He refers to the false self as something that “has been organised” (1967) and, in the “search for the self” the seeker has to make use of creativity to find this self again. As he says “it is in playing and only in playing that the individual child or adult is able to be creative and to use the whole personality, and it is only in being creative that the individual discovers the self” (Winnicott, D. 1971 73).

The counterpoint to essentialism (the idea of an essence within us) is existentialism which argues that “existence predates essence” (Sartre). In other words, we make ourselves through our actions in the context of our biological, social or political limits.

We are what we do

Sartre

Rather than searching for a past self that was buried or hoping to uncover our self through play and soul searching, we simply do things in the present/future: we take that holiday, pick up that book, or ask that person out for a coffee.

It is in the freely chosen actions that an authentic self emerges. Nothing to discover, uncover or unblock. Just choosing and doing.

The self as many

The true/false self proposes a continuum of possibilities across one single dimension. This may have been helpful in the 60/70s at the time of Winnicott, when so much of the collective experience was unified and there were only so many possible lives one could live.

However in our fragmented, postmodern society one can be and often is many things to many people. Increasingly, models in psychology and psychotherapy explore experience through the lens of qualitative distinct selves within us.

As Cooper explains, “by shifting from a ‘real man’ identity in his gym to a ‘new age identity’ in his men’s group to an ‘intimate man’ in his relationships, the postmodern man may be most able to engage with each of these diverse worlds.”

Where Winnicott would have seen a false self putting on the mask of a tough guy lifting weights, Copper recognises “a strategy through which the individual attempts to maximise the fullness of his or her being” (Cooper, M. 1999: 65)

Therefore, rather than attempting an exacting search for one elusive true self, we can embrace the possibilities of our postmodern society and explore ourselves in a variety of roles and ways of being.

The self as culturally constructed

The search for the true self can be an isolating experience. It is helpful to remember that Winnicott is theorising from an individualistic culture which often neglects to think about the role of others in our own being (beyond original families)..

But we exist in a network of relations to objects, people, concerns and purposes, as Heidegger proposed with ideas such as Being-in-the-world and Being-with (Bakewell, S. 2006)

Ultimately, we will find more satisfaction in our hero’s journey not as individuals but as co-created, relationally embedded beings. After all, living as social beings thrown into a collective upon which we depend (de Beauvoir) demands things of us so that we can satisfy our own needs. There is no search for the self, but rather a building of relationships through which we get to know ourselves.

The existentialist view that we exist in relation to others is original and provocative in modern Western philosophy. But it’s baked into other living traditions who place community at the heart of authentic living.

In Ubuntu philosophy, our identity and experience is inseparable from that of those around us, who foster our growth. Ubuntu translates as “I am because we are”. Professor James Ogude explains “agency does not only reside in individualistic self determining and autonomous bodies, but more importantly, in relationally, constituted social persons”.

And finally, we need to recognise structures of power, oppression and marginalization that create the bounds of our experience.

Our plans to travel to India on a search for your true self might have to be postponed to pay rent.

Then, it turns out paying rent may be where our true self emerges.

Bibliography

Beauvoir, S. de (1948) The Ethics of Ambiguity. New York: Philosophical Library.

Bolton, G. (2010) Reflective Practice: Writing and Professional Development. 3rd edn. London: SAGE Publications.

Cooper, M. and Rowan, J. (eds) (1999) The Plural Self: Multiplicity in Everyday Life. London: SAGE Publications.

Bakewell, S. (2016) At the Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails. London: Chatto & Windus.

Sartre, J.-P. (1956) Being and Nothingness: An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology. Translated by H.E. Barnes. London: Methuen.

Winnicott, D.W. (1965) The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment: Studies in the Theory of Emotional Development. London: Hogarth Press.

Winnicott, D.W. (1971) Playing and Reality. London: Tavistock Publications.

Winnicott, D.W. (1986) ‘The Concept of a Healthy Individual’, in D.W. Winnicott Home Is Where We Start From: Essays by a Psychoanalyst. London: Penguin Books, pp. 23–33.