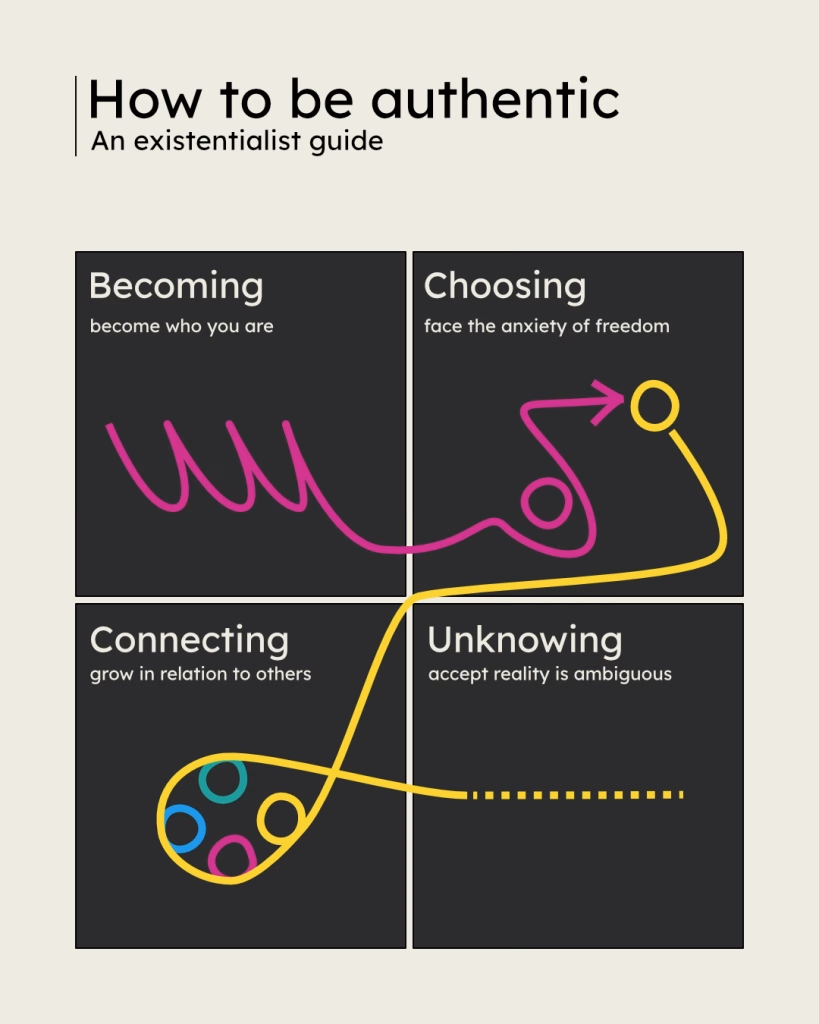

In this article I explore authentic living grounded in existential and other humanistic philosophies. It is anchored in four actions (becoming, choosing, connecting, unknowing) that challenge many of the popular ideas of what it means to be an authentic person.

What is it to be an authentic person?

Our popular understanding of being an authentic person often includes ideas like “being true to one’s values, ideas and personality”, “even at times when circumstances make that challenging”, “regardless of other’s opinions to the matter”.

As I will argue in this essay, this popular understanding is insufficient, misleading and risks being conducive to rigid neuroticism and interpersonal conflict. It traps people in caricatures of themselves, and limits their potential by encouragement of adherence to a self-image. Like Diogenes of Sinope, who lived in a barrel just to make a point.

Existentialists saw authenticity in a radical, deeper new way, grounded in an alternative way to understand human existence. And they argued that this way of authentic living made for sustainable ethics for our collective future in a way that our individualised faux-authenticity can’t.

Authenticity as becoming

In popular culture we favour stability of character. We despise political U-turns and distrust people who change their minds. We pay attention to role models and aspire to be like them. We build a self-concept and guide our actions to conform to it.

The problem with this is that we can become stuck: with the stress of dealing with a situation we don’t want, the boredom when we get the life we thought we wanted or somewhere in the middle: a rigid personality that is no longer serving us.

The solution that existentialism proposes for all scenarios is to see existence as a constant process of becoming.

Clients may be going through some of the hardest periods in their lives when they come to therapy. Difficult divorces, stressful work situations, long-term unemployment may overwhelm their emotional resources, making them wish they could just skip this difficult time and get over it.

But as Nietzsche hinted, these difficult periods are fantastic opportunities for growth and development. He said “I want to learn more and more to see as beautiful what is necessary in things, then I shall be one of those who make things beautiful”. (Nietzsche, 1974 : 223, translated from 1887)

Clients sometimes are in therapy for the opposite of a stressful situation: tedium vitae, an emptiness and boredom stemming from a lack of purpose, identity or direction.

For this scenario, we can take inspiration from Sartre.

He defines a person as “a being whose being is not to be” (de Beauvoir, 1947: 8). At every moment, it is dynamic and tries to move away from what it is. And it is in this movement, this “vain attempt to become God” (i.e complete, final), that we “become man”. The failure to ever become complete is our success to become human, as an emergent process.

Therefore, it makes no sense to ask if life is worth living, if our life matters. We make life matter through our actions, for which we are always free. We can, we always reinvent ourselves at each step.

And what about cases where someone isn’t totally stressed nor bored of life, but simply limiting themselves in important ways and unaware of it?

People often think that “having a personality” is the mark of an authentic person. But as Gabor Mate (2019 : 127) says, “much of what we call personality is not a fixed set of traits, only coping mechanisms a person acquired in childhood”. And these coping mechanisms, this “personality” ironically limit the potential of our personal development.

Simone de Beauvoir offered us a powerful alternative to the wish of having a magnetic personality. Reflecting on her best childhood friend she explained (1958 : 112) “she was said to have a personality: that was her supreme advantage (…) I preferred owning the universe than having a single face”.

Once we’re free from the need to be X, or more like Y, we can open up more possibilities for living.

Authenticity as Choosing

Some people may have a fear of making the right choice. Whether to get married, have kids, stay or leave. This fear can lead to anxiety and decrease life satisfaction.

But existentialism places focus away from the choices and into the choosing itself.

Sarah Bakewell (2016: 6-11) recounts Sartre’s famous story advising a young man to illustrate this point. Torn between joining the war efforts to defend France or staying to look after his mum, he despairs to make the right choice, and desperately seeks advice.

Sartre advises to focus on the freedom of choosing and the facing of inevitable anxiety that comes with it. It’s the brave choosing that makes him a person, more than the choice he may make. And to avoid the choosing – to completely outsource it to authorities, mentors or role models – will prevent his authenticity from emerging.

This inevitable anxiety is why people willingly give their freedom away. Sartre called this “bad faith”: a pretence that our choices are limited by things out of our control, or the embracing of roles that determine our behaviours.

Everyone uses bad faith in the narrative of their lives to avoid this dread; used excessively, it can paralyse us and seriously limit us. Hence, as Irvin Yalom says (1989 : 8) “the crucial first step in therapy is the patient’s responsibility for his or her life predicament”.

Empowering clients to face existential anxiety and make their own “choosing” and “be the author of their lives” (as quoted in Yalom 1989 : 8) can be a path of healing.

Authenticity as connecting

In popular culture we often see authenticity as an individual hero journey.

Inspired in popular culture, clients may see themselves in competition, difference or opposition to others. This can lead to isolation and a sense of not belonging.

Existentialism, as we have seen above, places radical importance in personal freedom and choice, but also understands authentic living as a necessarily socially embedded, relational process.

Isolating clients can be seen as navigating an existential crisis.

Heidegger reflected that a fundamental attribute of being is Being-in-the-world and Being-with. We exist in a network of relations to objects, people, concerns and purposes. Those who isolate themselves – ascetics, hermits, stylites are still defined in reference to the absence of those relations. And this position Heidegger considered defective.

People that are isolated have suffered a rupture with their natural connection to their Heideggerian Mitwelt (world-with, their existence in relation to others).

Karen Horney would agree with this idea of rupture. She argued that we need to “grow with others in love and friction” (1951 : 18) to become well adjusted individuals. Failing that, the person will develop a sense of isolation and will be “prevented from relating to others” (1951 : 18). This, for her, was the fundamental seed of human suffering.

Relational problems are therefore at the heart of all human problems.

Exploring how these clients feel safety, connection and belonging (or their absence) in relation to other people, and how meaning can be found through our purpose in the bigger world can be a path to genuine authenticity.

Sartre also thought about the necessary balance between individual and social existence in the idea of being-for-oneself and being-for-others. As Skye Cleary puts it simply of this Sartrean concept: “too much being-for-oneself would make us intolerable, too much being-for-others, a doormat” (2022 : 9). Neither is truly authentic.

The existentialist view that we exist in relation to others is original and provocative in modern Western philosophy. But it’s baked into other living traditions who place community at the heart of authentic living.

In Ubuntu philosophy, our identity and experience is inseparable from that of those around us, who foster our growth. Ubuntu translates as “I am because we are”. Professor James Ogude explains “agency does not only reside in individualistic self determining and autonomous bodies, but more importantly, in relationally, constituted social persons”.

Authenticity as Unknowing

We assume we know what is going on. Why someone is upset, what our friend is feeling, what our partner’s words mean.

But often these assumptions, born from our own emergence of being, prevent us from listening, understanding and ultimately connecting with the real experience of the other person.

Phenomenology is an orientation in philosophy that asks us to pay attention to things as we perceive them subjectively; taking away abstractions, judgements, assumptions and other meaning-making.

It helps us conclude that reality is ultimately unknowable because it is “inextricably linked to (…) our in-built, innate human species capacity to construct meaning” (Spinelli, 2005 :6).

It proposes a method whereby we put our assumptions in parenthesis to avoid mistaking our hypotheses for inherent elements of reality as they may be for other people too.

Because each of us experiences reality through our own meaning-making systems, each human is an “unique subject amidst a universe of objects” and this is “what he shares with all his fellow-men”. (Simone de Beauvoir, 1947 : 8)

This ambiguity, that we all are unique, helps us therapists accept a difficult but important truth: that only our client can know how he experiences the world, what their way forward may be, how they may give their own life meaning, how they can make their life matter.

Conclusion

As I have argued in this essay, our popular ideas about authenticity are dangerous propositions that can limit our potential, isolate us from others and justify unconstructive attitudes.

The existential alternative isn’t easy: we need to face the terrifying prospect of our ambiguous existence. But it empowers us to make our lives matter and give them meaning, and that effort is worth it in the long run.

Bibliography

- Bakewell, S. (2016) At the Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails. London: Chatto & Windus.

- Maté, G. (2003) When the Body Says No: The Cost of Hidden Stress. Toronto: Vintage Canada.

- de Beauvoir, S. (1959) Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter. London: Collins.

- Spinelli, E. (2005) The Interpreted World: An Introduction to Phenomenological Psychology, 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Yalom, I.D. (1989) Love’s Executioner and Other Tales of Psychotherapy. London: Penguin.

- Horney, K. (1951) Neurosis and Human Growth: The Struggle Toward Self-Realization. New York: Norton.

- Cleary, S. (2022) How to Be You: Simone de Beauvoir and the Art of Authentic Living. New York: Pantheon.

- de Beauvoir, S. (1948) The Ethics of Ambiguity. New York: Philosophical Library.

- Nietzsche, F. (1882) The Gay Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.