Simone de Beauvoir’s Ethics of Ambiguity is a pretty intense book.

I found it equal parts exhilarating, terrifying and confusing. I couldn’t put it down, but I also had to go back to read over it in frustration. I loved it and I hated it for being so mind-expanding and disarming. I think it has changed me. In a good, difficult way.

It was helpful that I read a few books that prepared me for it. Sarah Bakewell’s “At the existentialist cafe” offers a thorough introduction of existential ideas and the biographies of their authors. Skye Cleary’s “How to be you” is a user-friendly analysis of the idea of authentic living in de Beauvoir’s philosophy. And “Memoirs of a dutiful daughter”, de Beauvoir’s childhood autobiography, allowed me to understand her philosophical journey and the copious studying that preceded her career.

There are good summaries and analyses of this book online: here and here and of course Stephen West’s podcast in Philosophize this.

I will try to bring my own perspective by trying to assess implications for the practice of psychotherapy and personal development.

Overview of the book

I think the book is essentially divided in three parts

- A foundation based on (mostly) Sartre’s ontology. It defines existence as ambiguous, with no given values and full of inescapable paradoxes. That is the ground on which she will then lay a system of ethics.

- An exposition of the different ways in which we escape this ambiguity in specific human forms and personalities. These are defective positions and the implication is that they create suffering in ourselves and others.

- An exploration of what ambiguity means for ethics in practice, with a particular focus on moral freedom as the engine of ethics, and oppression as the key barrier.

As a very succinct summary: what she argues is that human existence is ambiguous and the only certainty is that each life needs to be lived by acting on individual freedom that enables the freedom of others.

In doing so, we need to engage in reflection to see what is the best way of doing that without resorting to given, absolute values.

It is therefore a methodology of ethics rather than a system of values (the only value is moral freedom that embraces individual and collective freedom at once).

The reason this is powerful from a wellbeing and therapeutic point of view is that it allows people to grow, adapt, reflect, build relationships far and wide and escape neurotic, rigid ways of thinking.

It expands the mind, delivers unknownness and reconciles the paradoxes built in reality such as the value of our own lives alongside the value of others.

Plus, it is radically empowering since it gives us the space to embrace our real nature: our lack of nature.

This means we can do and become anything we want, insofar as we will others to do the same.

Now, let’s pull apart the three sections to see how she destroys (partially or totally) what ethical systems were there before her and builds a new one from the ground up.

The ontology of human existence: being human is ambiguous.

Life is full of crushing and cruel paradoxes we can’t escape. This is where we should start; where “we should drive our strength from”.

- We can think anything (like wanting to live forever and be healthy and pain-free) but are trapped in a limited body in decay that prevents that.

- We experience ourselves intuitively as the only subject in a world of objects (others), but so does everyone else.

- A human life is all we have as the only subject in a world of objects and is therefore of sovereign importance, but also insignificant in the collective upon which it depends.

- We increase our mastery of nature, but by doing so we create forces that can limit us or even end us (the atomic bomb, generative AI).

This makes life ambiguous and pretty difficult to get our heads around.

Psychologists know that we struggle with lack of meaning. It’s built deep into our perception and cognition. At the most fundamental level we seek meaning and reject ambiguity. (Spinelli, 2005)

Hence we invent philosophical systems to reduce this ambiguity, give us easy to understand meaning, and narrow down our ethical choices. The State, God, Immortality, Economy, Private Property. But they all are based on the fundamental falsehood in that they are given or absolute values; that they are essential to human nature.

The existentialists’ core claim is that existence precedes and conditions essence (Sartre, 1943). We make ourselves through our choices. We get to choose our values. There is no God to give them to us. So “it is not a matter of being right in a God’s eyes, but in his own eyes”.

As she also says “the genuine man will not agree to recognise any foreign absolute”. (de Beauvoir, 1947: 13)

But, and this is important, this doesn’t make existentialist ethics a subjective ethics system, meaning “everyone does what they want”. She is simply daring to destroy the illusion of given or absolute values to see how a method of ethical decision-making could be devised from the ruins.

And to do this we need to go to the roots of what it is to be a human being.

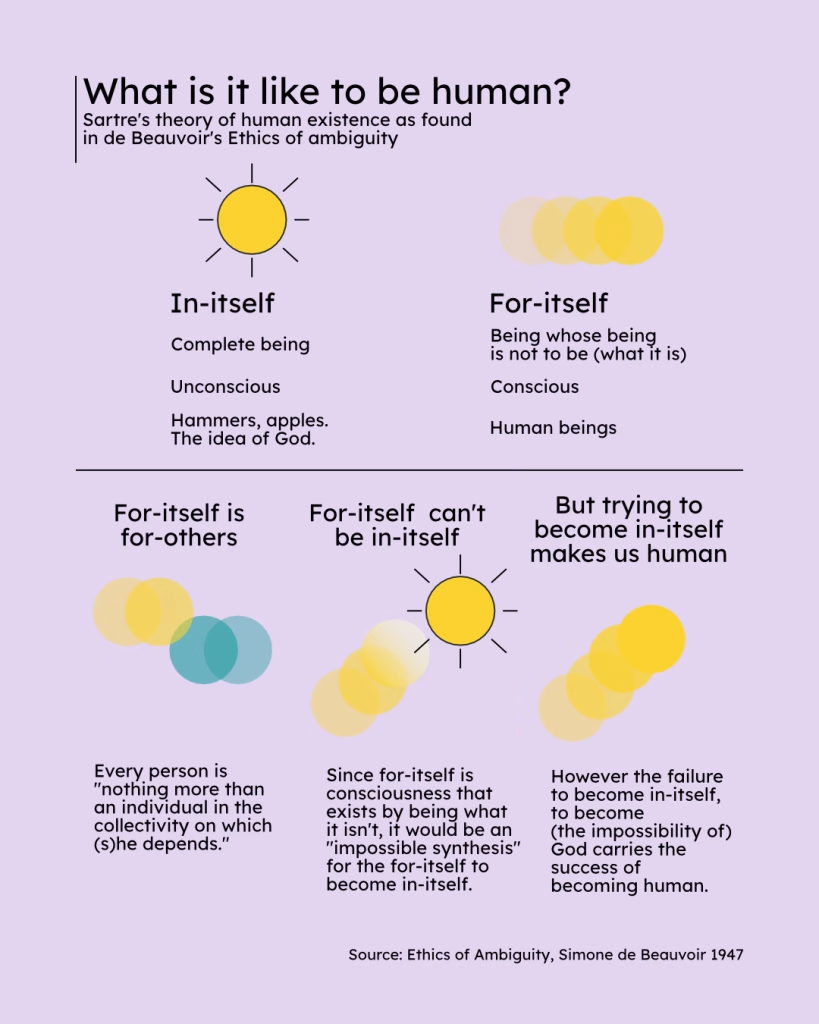

So what does it mean to exist? Here de Beauvoir resorts to Sartre’s ontology that distinguishes:

- In-itself – an object that is pure, perfect, unconscious. It has no agenda to go anywhere or to become anything that it already isn’t. On the one hand, hammers and apples are in-itself. But also the idea of God in its plenitude is in-itself.

- For-itself – a self-conscious subject whose “being is not to be”. These are us humans, who create ourselves through every action, destined to change ourselves, to be what we aren’t, to disclose our being, our engaged freedom to try to become whatever we want. We rest because we are tired, we scratch because it itches, we clean the kitchen so there are no fruit flies around.

The fundamental issue of unambiguous ethics – where given values are observed as absolute – is that humans try to become in-itself as an end. To aim at moral perfection, enlightenment, to be X.

And being is not what we are. We exist, meaning, we lack being so that there might be being through engaging our freedom to grow, change, “disclose our being”.

Think: movement.

But this is the good bit. It is OK to aim to be an it-self if we understand the impossibility of it. If we accept that failure is built into this effort. Because this failure has success in it as well. It’s the exercise of our nature as a lack of nature.

So we aim for plenitude (the better job, the person we love, the holidays we crave), only insofar as what we seek is the exercise of our freedom. It is “in its vain attempt to be God that man becomes man” (de Beauvoir, 1947: 11). It is “by uprooting himself from the world, man makes himself present to the world and makes the world present to him”. (de Beauvoir, 1947: 11)

This is the fundamental issue at heart. We exist as ontological freedom, with no given values. There is no human nature other than exercising this freedom of being through the negation of our being. And this creates mind-boggling ambiguity that makes existence both empowering (radically free) and terrifying (radically uncertain).

She closes this chapter by proposing that if humans have no essential nature (beyond overcoming their momentary state of being), evil has a place in the world as well as good. It is by escaping from freedom that humans create evil and suffering.

Because this is so uncomfortable, we try to deny it. This creates suffering for ourselves and others (as above). The focus of the next section is to explore the ways in which it happens and the type of personalities it gives rise to.

Later in the third section, we will look at the alternative: how to live in a world without values but with a method to create them.

“is in its vain attempt to be God that man becomes man”

Escaping ambiguity: defective ways of being vs freedom

In this section, she exposes different ways in which humans try to escape this ambiguity.

To start with, she considered the issue developmentally.

The child is metaphysically privileged and unburdened of genuine freedom. This makes adolescence especially difficult, as the reality of freedom begins to unveil itself. The individual starts to feel the weight of their actions and their consequences, often triggering an existential crisis.

When the child starts feeling his subjectivity, he may react in different ways in becoming an adult. The type of person they become depends on their strategies to avoid freedom, or readiness to accept it in all its ambiguity.

De Beauvoir proposes these defective positions, in order:

- Sub-man

- Serious man

- Nihilist

- Adventurer

- Passionate

The sub-man

The sub-man is at the bottom of the ladder. They experience a dull world to justify his lack of existence. They oppose the projects of other people, and love to find groups of people to hate or complain about: inmigrants, politicians, conservatives, hippies, transgender, homosexuals, snobs – anything is possible depending on the context.

The sub-man is a starting position for adolescents that haven’t been able to find purpose yet.

And it could also be the position that adults may fall into in despair.

Here, the image of a retiree that went through life as a serious or passionate person and now inhabits life without their object of purpose/distraction comes to mind. Here is a good story from Arthur Brooks to illustrate this.

The serious man

The serious man is someone who finds values and purpose in an external object which they consider absolute, by “submerging his subjectivity (…) in the content from society”.

It is not the intrinsic nature of the object that matters, but the act of losing himself within it. They consider the object essential and themselves as inessential.

The serious man in therapy is likely to present with anxiety, rigidity and lack of spontaneity.

As an example, consider a vegan man. Landing on the idea that consuming animal products is morally unacceptable, he develops a new lifestyle in accordance to this. One the one hand, they make friends with other vegans and bond over this moral stance. On the other one, he isolates himself as they judge non-vegans and prefers the company. However veganism is so ingrained in his personality that he could never let it go or see how he has fallen prey to seriousness.

Alternatively, consider a devout Christian lady, painfully aware of all the instances where others aren’t following the “word of (her) God”. She is now at odds with a child who has moved in with her girlfriend “in sin”. Unable to look past her own values, she complains of a strained relationship and abandonment.

The example could work with any other external object of absolute values: Marxism, work, volunteering, a neighbour assembly, saving the whales or any type of political affiliation can play the same role.

Nihilist

In contrast, the nihilist rejects seriousness, but fails to embrace their freedom as an opportunity to actively create himself through choice and action. They are right to think the world is without inherent meaning, but fail to understand it is up to them to give it meaning.

In therapy, the nihilist may present with depression, anhedonia and/or addiction.

As an example consider an artist who, after some early success fails to sustain it. Now, they hardly engage with art and anything else. They have lost any interest in life, projects or relationships because “what’s the point”.

The adventurer

The adventurer also rejects seriousness, perceiving the world as a realm of endless possibilities.

Often emerging from a privileged or joyful childhood, the adventurer asserts his being by continually transcending it. This attitude is close to moral engagement, but adventurers often have an incapacity for connection with others.

The adventurer’s danger lies in his belief that one can act entirely for oneself, independent of or even against others. This can lead to alliances with oppressors who treat others as mere objects to fulfill personal desires. As de Beauvoir writes, “His fault is believing that one can do something for oneself without others and even against them” (68).

In therapy, the adventurer is likely to present with deep boredom and existential anxiety towards death, illness, aloneness or lack of meaning.

As an example, consider an entrepreneur. Now in her 50s, she is financially secure but complains of a bitter divorce and a lack of genuine friendships. She has many stories of company exits, faraway travels and endless festivals. But as she approaches retirement she is showing signs of existential despair and a lack of enjoyment.

The passionate

The passionate man is a better version of the serious man in that their external object is a creation of their subjectivity.

Though he may later become serious about this pursuit, his passion originates inwardly. The fault of the passionate man is that he wills himself “not to be,” not in order to bring about true being, but merely to attain or sustain an abstract, fixed state of “being”.

Workaholics, especially of a creative or otherwise purposeful nature may often be passionate.

In therapy, the passionate may be experiencing an existential crisis as a result of an inability to practice their passion through retirement, unemployment, injury or any other change in situation. Or they could have simply lost their passion if it was sustained by seriousness (for example a passionate doctor who had only gone into medicine due to familial pressures).

In essence, each personality improves on its previous iteration, in a zigzag of defective personalities that fail to embrace freedom as it really is.

- The sub-man is a total failure to find meaning

- The serious man finds meaning in external objects considered essential

- The nihilist doesn’t fall for the serious world, but rejects meaning altogether

- The adventurer finds meaning in the joy of action but without accepting the need to will the freedom of others to attain theirs.

- The passionate find meaning in the disclosing of their own subjective being but they are unable to tolerate the ambiguity of the pursuit and therefore seek to possess their passion and achieve a fixed state of being.

In contrast, a free person:

- Recognises the need to create their own value make up and constantly re-evaluate it.

- Accepts the reality of being an emergent process of becoming that is never complete or finished. They thrust their being into the world.

- Understands that genuine freedom wills the freedom of others.

How to live: ethics in practice

In the third section, de Beauvoir now lays down the possibility of an ethics system.

The triumph of ethics is to improve the world, to bring spirit into nature so that new possibilities can emerge.

She proposes the beautiful thought of seeing endeavours such as science, technology, art and philosophy as rightful domains for what de Beauvoir considers the engine of ethics: the moral freedom of thrusting ourselves into the world. In neither domain, we are sure to never reach the end. But we always improve the quality of our lives either by participating in its disclosure or enjoying the way others give us their creations.

But politics, where life and death takes place, is more complicated.

Having destroyed the possibility of simply upholding given values as external absolutes, we are left with freedom. But she urges to consider freedom in its totality, as the parallel acts of willing the disclosing our being while “with the same movement try to free men, by means of whom the world takes on meaning.” (79)

This focuses the chapter on the misunderstanding of freedom: oppression.

The oppressor exercises their right to disclose their being without taking consideration, and/or opposing the freedom of others to do the same. They are “dishonest, in the name of his seriousness or passions (…) he refuses to give up his privileges”. (104)

How do we bring the idea of freedom and oppression to the world of therapy?

Firstly, we need to open our minds to the damage inflicted by an oppressive society (scared of freedom and ambiguity). Some clients will have a history of trauma and current challenges due to their intersectionality. Studying and observing the specific ways in which different oppressed minorities suffer their attacks on freedom is a great way to develop compassionate understanding and decrease risks of cultural misunderstanding.

Secondly, we can consider freedom/oppression at the very core of traumatic experiences. Clients who have had their freedom limited – by abusive families, partners or other relations – will have trouble exercising their freedom and likely engage in ways of being and behaving that create self-imposed limits. Horney’s theory of personality development is a great example of this.

Ethics of Ambiguity is by no means an easy book and neither are its implications. But it is a piece of work that seems able to stand the test of time and give us a way to think about politics, ethics and existence.

Bibliography

Beauvoir, S. de (1948) The ethics of ambiguity. New York: Philosophical Library.

Sartre, J.-P. (1956) Being and nothingness: An essay on phenomenological ontology. Translated by H.E. Barnes. London: Methuen.